If you have been keeping up with the SMURF news so far this summer, you may have noticed a trend – we haven’t been catching many fish lately. With less than two dozen fish caught in the last three weeks, one might start to wonder what causes lulls in fish recruitment? For the SMURF team, catching few fish is just as informative as catching many. As discussed in previous posts, the low numbers in the SMURFs are in line with what we expect for this time of year. But why do we expect to see so few fish during this time of the summer? It’s the height of tourist season, why shouldn’t it also be the height of fish recruitment season?

When fish settle is highly dependent on reproduction schedules. A high proportion of the fish we collect in SMURFs are rockfishes of the genus Sebastes. Rockfishes are somewhat unusual in their method of reproduction. Many fish reproduce through external reproduction, where males and females release sperm and eggs into the water column or onto rocks. Rockfishes, however, utilize internal fertilization, so that embryos develop inside females, who then release many living larval fish all at the same time. Some species release over 100,000 larvae at once! These larvae are generally microscopic, and we do not monitor them via SMURFing. However, over the span of a few months, the larvae grow and develop into the juveniles we collect in SMURFs.

Timing is Crucial

The crucial element of this cycle is timing. Different species give birth at different times of the year. For example black rockfish release their larvae mostly between February and May. The larvae spend about 3-6 months in open water before settling nearshore in the early summer months of May and June. Coincidentally, this is when we tend to see the biggest pulses of OYTBs (a group of species including black rockfish) in the SMURFs. For example, in early June of this year 426 OYTBs were collected at Redfish Rocks Marine Reserve! As time passes, black rockfish grow and move to deeper waters, below the SMURFs. Thus, we see fewer as the summer goes on.

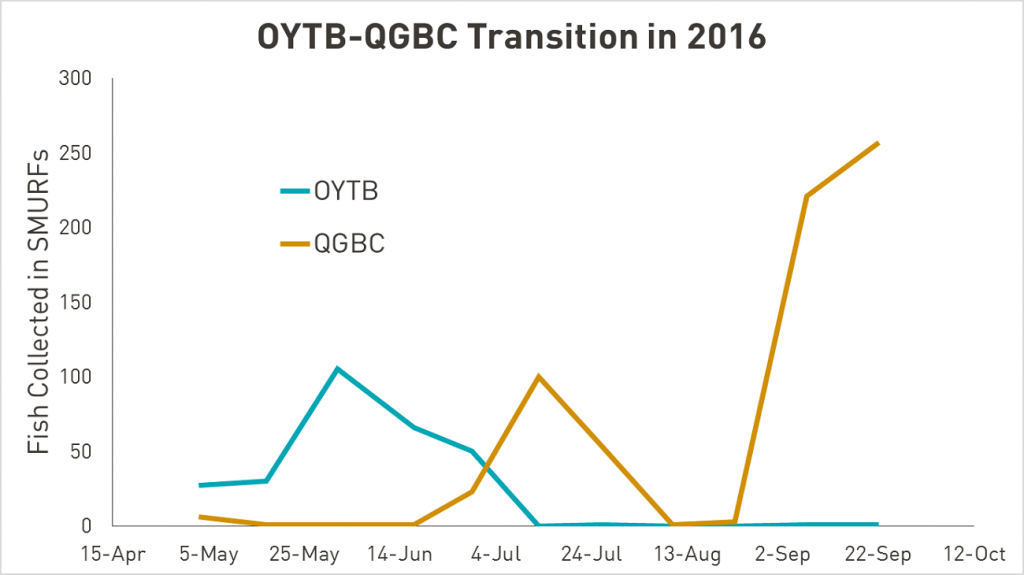

Figure 1. A brief lull can be seen in early July in this SMURF data from 2016. It shows the transition from collecting one species group to the next and goes from OYTBs (olive, yellow, and black rockfish) to QGBCs (quillback, gopher, black-and-yellow rockfish).

Conversely, quillback rockfish tend to release their larvae later, between the months of April and July. While we’re hauling in OYTBs in the early summer, quillbacks are still too small for collection. After a few months in the water column, they begin to settle later in the summer around late July to August. In many years, QGBC (species grouping including quillbacks) pulses have occurred towards the end of July and through the months of August and September. Our greatest haul of QGBCs occurred in September of last year at Otter Rock Marine Reserve when 257 were collected!

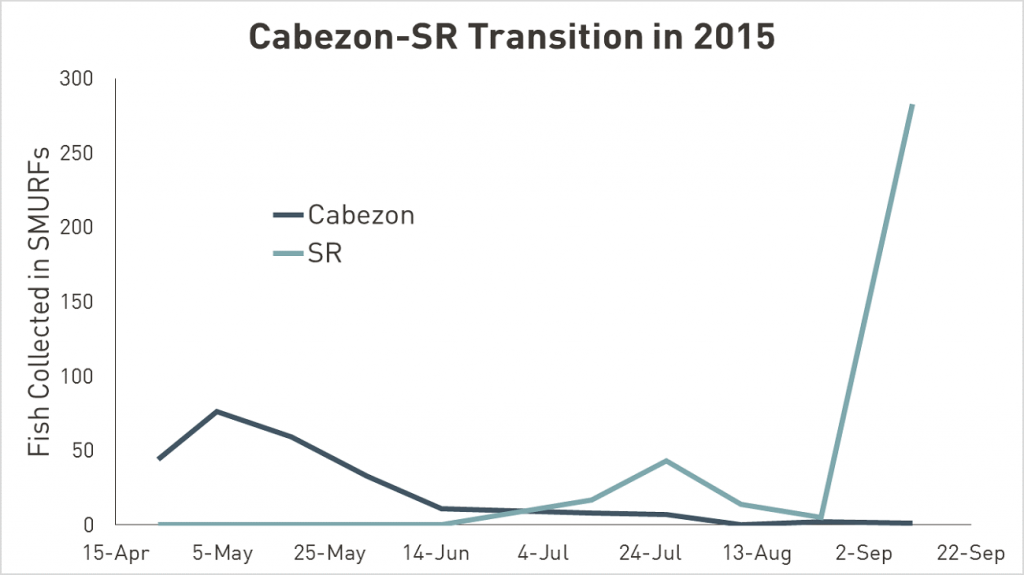

The OYTB-QGBC transition, in the graph below, is a perfect example of how reproductive schedules are partially responsible for the mid-summer lull. A similar pattern can be described for other species, such as the cabezon-splitnose/redbanded (SR) transition. Cabezon (which reproduce via external fertilization), spawn in the winter between November and March. After a few months in the water column, juveniles are collected in greatest numbers at the beginning of the summer. Splitnose and redbanded rockfishes (the two members of the SR species grouping) don’t tend to release larvae until spring. We sometimes see huge pulses of these species in late summer, including an enormous pulse of 538 SRs in September 2013!

Figure 2. This data from 2015 illustrates another species transition as the summer progresses. This transition is from collecting more cabezon to an increase in the SR group (splitnose and redbanded rockfish).

This Week’s Summary

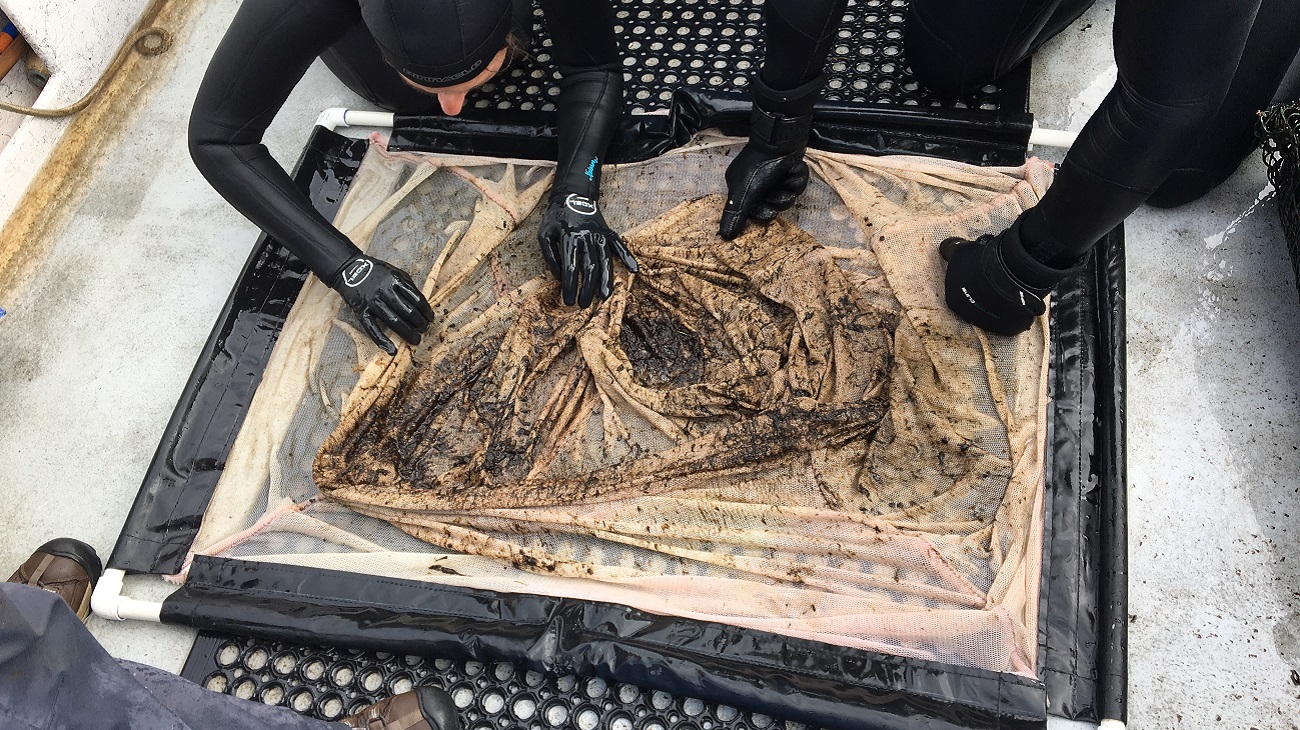

SMURFing this week returned slightly fewer fish than that outing in 2013. In total, 3 fish were collected – 1 cabezon and 2 clingfish – from Otter Rock. Conditions were some of the roughest we’ve encountered according to a seasoned SMURF veteran, with steep waves and substantial currents. However, thanks to expert piloting by the boat captain of the Shearwater, strong swimming by the snorkelers, and plenty of help from the deck crew, SMURFing went off without a hitch. Just another day at the SMURFfice. It’s possible that oceanic conditions could affect the number of fish collected, so we assess current flow at each SMURF. Other factors that may contribute to the midsummer lull include upwelling and variation in reproductive patterns between years. As more and more data are collected from year to year, our understanding of when fish show up in the SMURFs will continue to grow.

If you’re hungry for more SMURF knowledge. You can check out this leaflet, or look back at our previous SMURF posts about the SMURFers, fish sampling, and researching the reserves. And make sure to keep coming back in the upcoming weeks for more awesome SMURF science!

Love, Milton S., Mary M. Yoklavich, and Lyman K. Thorsteinson. The Rockfishes of the Northeast Pacific. Berkeley: U of California, 2002. Print.

O’Connell, Charles P. “The Life History of the Cabezon Scorpaenichthys Marmoratus.” 1953. State of California Department of Fish and Game Marine Fisheries Branch Fish Bulletin 93. Online Archive of California. Web.