By Guest Contributor Vaughn Robison

There are deep, sometimes unfathomable relationships to areas of the ocean now encompassed by Oregon’s marine reserves. Our series, Returning to the Reserves, shares the stories of coastal residents who forged a relationship with an area in one capacity prior to its designation as a marine reserve, but later returned to it in another role. We profiled a fisherman who returned as science collaborator, an urchin diver-turned fisheries scientist who returned as a research field station manager, and an ecologist from an environmental non-profit who has returned each field season as part of long term monitoring projects. Their expanded roles and rich histories of attaching to and depending on these areas offer insight and understanding of the reserves and their impacts on people.

These impacts, we found, varied dramatically from one person and one marine reserve to the next.

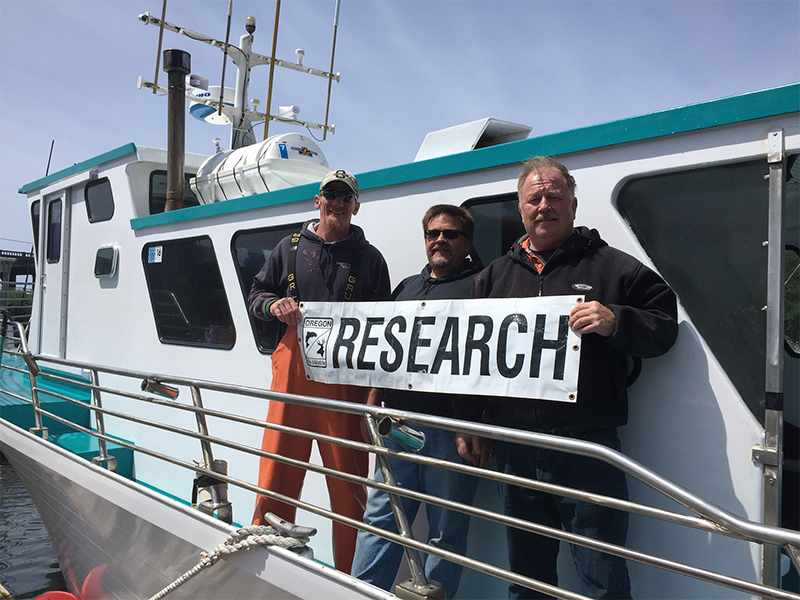

According to late charter boat captain Lars Robison, the area that became Cascade Head Marine Reserve was always his backup. The waters were his reliable last-ditch fishing spot in a five-decade career as a charter boat captain. This meaning endured even after the marine reserve was closed to fishing and while Robison chartered lead hook and line surveys that monitor changes to the fish populations within the reserve area. On these research excursions, Robison expressed excitement to witness potential changes and cautiously hoped the area would lead to fish populations spilling over into other areas of the ocean. As a marine reserve, Robison still thought of his backup fishing spot as a safety net.

Along with Robison’s unyielding meaning of the area, his level of attachment to the area also endured. This rigid attachment is despite its new conservation objectives and his new role that worked toward achieving them. “It didn’t make me care any more or less about the place,” he says of revisiting the marine reserve to monitor its fish populations after being displaced from the area as a fisherman, “I’ve always cared about the place.”

For Tom Calvanese, the meaning of the waters that became Redfish Rocks Marine Reserve has evolved alongside his many roles within them. As the manager of Oregon State University’s Port Orford Field Station, Calvanese draws upon his history in the area as an urchin-diver-turned-fisheries-scientist to facilitate educational experiences for university students and researchers and the public. This somewhat amorphous meaning is in part a culmination of the roles he has performed and the capacity he has helped build around them within the reserve’s well-defined boundaries. What was once a prized fishing spot became a marine reserve, a living laboratory, an interactive classroom, and a hub of community engagement. “I see these things as all interconnected,” said Calvanese.

This interconnected meaning is also how Calvanese shares his intersectional attachment to the place with the students he mentors at the field station. His mentee, Tom McCambridge, credited Calvanese for nurturing his understanding of the area. “I’m here working on conservation alongside the fishermen…which is really cool,” explained McCambridge before sharing an early cut of an educational video he created as part of his marine reserves interpretation internship.

For Dick Vander Schaaf, an ecologist from The Nature Conservancy, the importance of Cascade Head and Cape Falcon marine reserves were codified with their designations as protected areas. To him, their designations secured the importance of the places as ecological marvels while connecting new marine protections to the existing protections on land. This coupling helps develop comprehensive protections between dynamic ecosystems whose relationships are not constrained by their boundary lines on maps.

His attachment to these places, he explains, compounds with each returning field season to monitor the areas. By returning from one season to the next, he not only contributes to important ecological understandings of these areas, but also to improved skills to monitor them that are nurtured intimate relationships with these places.

The variability of these connections is not unexpected given the variety of roles these individuals have played within each marine reserve location. However, hearing their stories provided us with a deeper understanding of just how nuanced these relationships between people and places can be, and how these connections manifest through their work in these areas. We look forward to exploring these connections more in the future through our various Human Dimensions studies. The relationships that Oregonians have with the state’s marine reserves truly are unfathomable sometimes, but we’re committed to diving deeper to better understand them.