Oregon’s rocky reefs are highly valued as productive habitats for nearshore fishes. But, collecting information about these important areas, and the fish that live there, has become a challenge for researchers. These shallow, rocky areas can be difficult to access and murky with poor visibility. From a fish’s standpoint, that’s a pretty ideal habitat. However, it leaves researchers scratching their heads as to how to best collect data that is integral to monitoring nearshore waters.

Traditional research techniques, such as trawl surveys, are not appropriate (trawls get snagged over rocky habitat). Other research techniques, such as hook-and-line surveys, are an option, but this extractive method selects for larger individuals (juveniles can’t bite a large hook) and offer limited habitat data. Video surveys offer a cost-effective, non-extractive means for collecting valuable data on the entire fish population including smaller individuals and give researchers a glimpse of the habitats these fish call home. For that reason, video surveys are an integral component of nearshore ocean research and monitoring in Oregon.

ODFW has a strong research arm that has paved the way for premier video survey method development. Recently, the ODFW Marine Reserves Program completed a pilot study designed to test a new camera video lander configuration that is both light-weight and cheap to build to more readily survey shallow, rocky, nearshore reefs. However, this survey method isn’t without its own suite of challenges.

ODFW has a strong research arm that has paved the way for premier video survey method development. Recently, the ODFW Marine Reserves Program completed a pilot study designed to test a new camera video lander configuration that is both light-weight and cheap to build to more readily survey shallow, rocky, nearshore reefs. However, this survey method isn’t without its own suite of challenges.

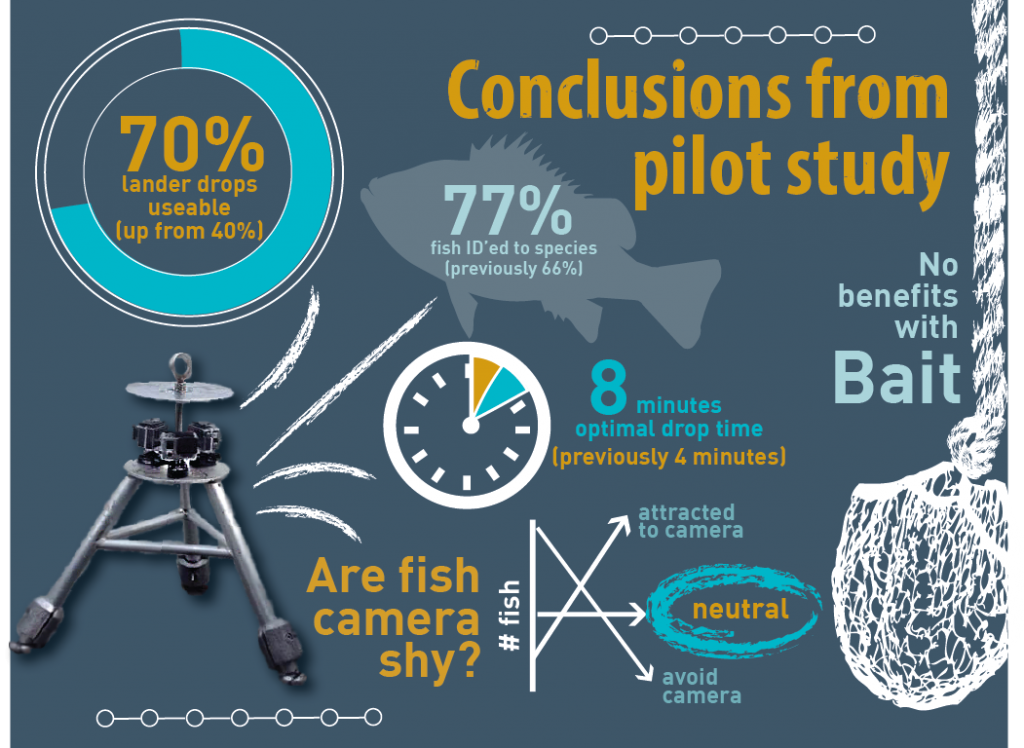

Like all scientific research, there are lingering questions about potential biases, such as: are different fish species attracted to the camera, or do they avoid it? Or, does using bait make it easier to identify fish species or allow us to see more species? And, what is the optimal amount of time a camera system should sit on the ocean floor? Results from the pilot study conducted by the ODFW Marine Reserve Program addressed these exact questions and had some surprising results.

First, fish behavior studies did not find any species fleeing the camera system or particularly attracted to it. Rather, most fish seemed unaffected by this new apparatus entering their home—a good thing for collecting unbiased data on species abundances. Second, while bait has been useful in increasing the numbers and diversity of fishes observed in other lander systems around the globe, here in Oregon, baiting the lander did not show the same trends. Bait did not increase the species diversity or abundance of fish captured on the video, nor improve the team’s ability to identify the fish to species. There has been discussion among researchers about the amount of time a camera system should stay on the seafloor to get an accurate picture of the fish that are really out there. Interestingly, this pilot study suggests that 8 minutes is optimal to get a representative sample of fish populations at a nearshore study site.

Ultimately, these results help scientists better understand strengths and limitations of video surveys. And, small-scale pilot studies are particularly important to the scientific process. While it is impossible to count every fish in the sea, researchers strive to collect small amounts of data that gives an understanding of larger-scale populations. In other words, they want to make sure the snapshot they are seeing is representative of what actually exists in the ocean. Small-scale pilot projects work out ‘kinks’ in scientific methodology so that when, and if, large scale surveys happen, they paint an accurate picture of our nearshore ocean environment.

The Marine Reserve Program has published the results of this pilot in the Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. Next steps for these new landers will be to add stereo-video capacity to allow us to gather precise size data on the fishes observed, further enhancing the data collected from video lander tools in the marine reserves.

Diver Training Update

During February, the ODFW Marine Reserves Program partnered with the Oregon Coast Aquarium and Oregon State University to host our annual scientific diver training. During this training, existing scientific divers refined their skills. The divers reviewed methods for counting fish, invertebrates and algae to species in Oregon’s nearshore waters using the established Partnership for the Interdisciplinary Studies of Coastal Ocean (PISCO) subtidal survey methods.

Trained divers are an integral part of the Marine Reserves research (read more about scientific diving here). Ten new scientific divers are have completed their initial training to help conduct Oregon SCUBA surveys in Oregon’s marine reserves.

Thank you Hilarie, Rhoda, Nate, Jackie, Aaron, Alissa, Will, Taylor, Brittany, and Jessie for all your hard work and commitment during the training process. Welcome to the Marine Reserves Dive Team!

Photo: Inside looking out, scientific divers train inside a tank at the Oregon Coast Aquarium.